This is an email sent to a person who requested a copy of the powerpoint presentation I did on Observation Reliability where I presented my new idea about the sequence from research to standards to indicators to data collection to teacher support and evaluation. If you’d like to see the Powerpoint send me an email.

When I first wrote eCOVE I was focused on giving helpful feedback to student teachers. From years of working with student teachers and new teachers I knew that they needed help thinking through the problems that came up in their classrooms. Providing them with ‘my’ answers and ideas was of much less benefit that getting them to think through things and devise their own solutions.

I also knew, again from personal experiences working with them, that giving them data (pencil and paper before eCOVE) help them honestly reflect on their own actions and outcomes, and it also greatly diminished the fear factor that came with the ‘evaluator’ role of a supervisor.

When I first started working with administrators and eCOVE I was totally focused on changing their role from judge to support and staff development. I preached hard that working collaboratively would have great effects and would/could create a staff of self-directed professionals. I still strongly believe that, and have enough feedback to feel confirmed.

However, a recent conversation with an ex-student, now an administrator, has added to my perspective. He likes eCOVE and would love to use it except that his district has a 20 page (gulp!) evaluation system that he needs to complete while observing – so he doesn’t have the time to work with teachers. We agree that it’s a waste of time, and corrupts the opportunity for collaborative professionalism.

As I thought about his situation and the hours of development time that went into the creation and adoption of that ‘evaluation guide’, I realized that my approach to observation as staff development had ignored the reality of the required and necessary role of administrator as evaluator. The guide that he’s stuck with seems to me to be the main flaw in the process, and what I believe is wrong with it (and the thousands in use across the country) is that they ask the observer to make a series of poorly defined judgments based on a vaguely defined set of ’standards’. It’s an impossible task and is functionally a terrible and ineffectual burden on both administrators and teachers.

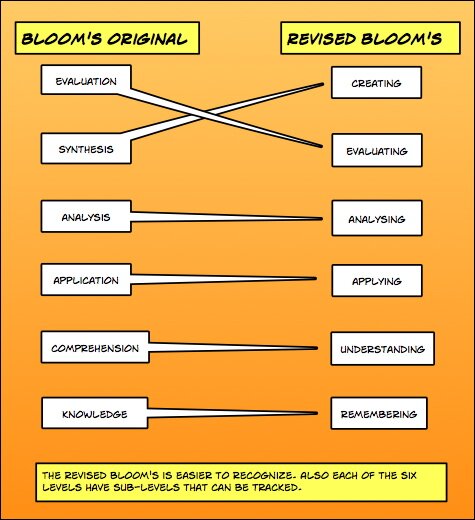

When I thought about how a standards based system might be improved, I developed the basis for the idea in the powerpoint – Standards should be based on research; the implementation of the standard should be in some way observable, if not directly then by keystone indicators; the criteria for an acceptable level of performance should be concrete and collaboratively determined. I say collaboratively since I believe that administrators, teachers, parents, and the general public all have value to add to the process of educating our youth. Setting those criterial levels in terms of observable behavior data should, again, be based on research, and confirmed by localized action research efforts. That’s not as difficult as it sounds when the systematic process already includes data collection.

For the last couple of years, whenever I presented eCOVE I made a big point of saying that I was against set data targets for all teachers, that the context played such a big part in it all that only the teacher could interpret the data. I think now that I was wrong about that, partially at least. A simple example might be wait time – the time between a question and calling on a student for an answer. There’s lots of research that shows a wait time of 3 seconds has consistent positive benefits. While I’m sure it’s not the exact time of 3 seconds that is critical, the researched recommendation is a useful concrete measure. If a teacher waits less than one second (the research on new teachers), the children are robbed of the opportunity to think, and that’s not OK. An important facet of the process I’m proposing has to do with how the data is presented and used. My experience has been that the first approach to a teacher should be “Is this what you thought was happening?” This question, honestly asked, will empower the teacher and engage him or her in the process of reflection, interpretation, and problem solving. During the ensuing professional level discussion, the criteria for the acceptable level of student engagement is a 3 second wait period should be included, and that’s the measure to be used in the final evaluation. For, in the end, a judgment does have to be made, but it should not be based on the observer’s opinion or value system, but on set measurable criteria — criteria set and confirmed by sound research.

A more complex example – class learning time. The standard illustrated in the powerpoint stated that ’students should be engaged in learning’, a commonly included standard in most systems. There is extensive research that indicates that the more time a student is engaged in learning activities, the greater will be the learning. While the research does not propose a specific percent of learning time as a recommended criteria, I believe we as a profession can at least identify the ranges for unsatisfactory, satisfactory, and exceptional. I think we’d all agree that if a class period had only 25 % of the time organized for teaching and/or student engagement in learning activities, it would be absolutely unsatisfactory. Or is that number 35%? 45%? 60%? What educator would be comfortable with a class where 40% of the time lacked any opportunity for students to learn. I don’t know what the right number is, but I am confident that it is possible to come to a consensus over a minimum level. Class Learning time is a good example of a keystone data set – something that underlies the basic concept in the standard ‘engaged students’. I know there are others.

But then my personal experience as a teacher comes into focus, and the objection “How can you evaluate me on something I don’t have full control over?” pops up. I remember my lesson plans not working out when the principal took 10 minutes with a PA announcement and there were 4 interruptions from people with important messages or requests for information or students. How could it be fair to be concerned about my 50% learning time when there were all these outside influences?

That would be a valid concern where the evaluation system is based on the observer’s perception and judgment, but less so when based on data collection. It is an easy task to set up the data collection to identify the non-learning time by sub categories – time under the teacher’s control and time when an outside event took the control away from the teacher. The time under the teacher’s control should meet the criteria for acceptable performance; the total time should be examined for needed systematic changes to provide the teacher with the full allotment of teaching/learning time. Basing the inspection of school functioning on observable behavior data will reveal many possible solutions for problems currently included in the observer’s impression of teaching effectiveness.

It’s reasonable to be suspicious of data collected and used as an external weapon, and for that reason I believe it to be critical that the identification of the keystone research and indicators, and the setting of the target level be a collaborative process. Add to that the realization that good research continues to give us new knowledge about teaching and learning, and with that the process should be in a constant state of discussion and revision. That’s my vision of how a profession works – critical self-examination and improvement.

So now my thinking has come to a point where I believe (tentatively, at least) that we have sufficient research to develop standards, or to better focus the standards we do have; that we can identify keystone indicators for those standards; that we can use our collective wisdom to determine concrete levels for acceptability in those keystone indicators; that we can train observers to accurately observe and gather data; and that that data can be used to both further the teacher’s self-directed professional growth and to ensure that the levels of effective performance as indicated by sound research are met.

I’m hoping that my colleagues in the education field (and beyond) will join in this discussion and thinking. What is your reaction? Can you give me “Yes, but what if…..?” instances? Do we really have the credible research to provide us with keystone indicators? How could a system like this be abused? How could we guard against the abuse?